April 18, 2024

Programs that could help keep Massachusetts children out of foster care are struggling for money

BY The Boston Globe

Thousands of Massachusetts parents face scrutiny from the state’s child protection system and, with it, the all-consuming fear of losing custody of a child.

For many of these families, poverty — and not bad parenting — is at the root of neglect allegations. Those same financial circumstances prevent families from advocating for themselves or finding services that could help stabilize their lives. But for the past 2½ years, they’ve had some help in Massachusetts, through the efforts of lawyers and social workers who developed four small programs, the Family Preservation Project, meant to help parents with open Department of Children and Families cases keep custody of their children.

The programs, though, may need help themselves as they face a financial cliff this summer. A two-year, $1.4 million federal pandemic relief grant is expiring at the end of June, and leaders of the nascent programs are not sure where they’ll find the money to keep operating, much less expand, to meet families’ needs in a state where children are placed into foster care at a rate that consistently exceeds the national average.

“It’s going to need sustainable funding,” said Susan Elsen, an advocate with the Massachusetts Law Reform Institute. “It’s exactly what everybody knows is needed to shore up these families who could safely parent their kids if they have the help they needed.”

The organizations that run the four programs, active in the Boston region, New Bedford, Lynn, Lawrence, Lowell, Springfield, and as of this year Worcester, see themselves as part of a national movement to reform the child welfare system by introducing more due process and support for parents.

The family preservation programs include lawyers, social workers, and parent advocates who work together on behalf of parents. Lawyers involved with family prevention programs emphasized they do not take cases where DCF has substantiated claims of physical or sexual child abuse, but noted neglect cases make up the vast majority, more than 86 percent, of the child victims DCF oversees.

There is also a racial imbalance in the state’s child protection system, with Black and Latino children overrepresented among kids in foster care.

The programs tackle the reasons behind neglect findings, which can include lack of child care or housing, while also connecting parents with social services.

“We’re really trying to uncouple poverty from neglect,” said Madeline Blanchette, senior supervising attorney with Community Legal Aid, and director of the Springfield family preservation program.

Though just 110 families have participated in the programs since the first debuted in 2021, the results have been encouraging. Out of all the children involved in the program, just two ended up being removed from their homes.

A DCF spokesperson said it would be difficult to provide a comparable number of the share of total neglect cases that result in a child’s removal. Overall, about 20 percent of DCF’s cases result in a child’s placement outside their home, but that includes cases of physical and sexual abuse.

Lawyers with the Family Preservation Project can negotiate how much access DCF has to families. For example, the agency can request full access to everything discussed in therapy sessions, which can discourage people from being fully forthcoming, Blanchette said. She has in some cases restricted the state agency’s access only to information revealed in therapy that is pertinent to the neglect finding.

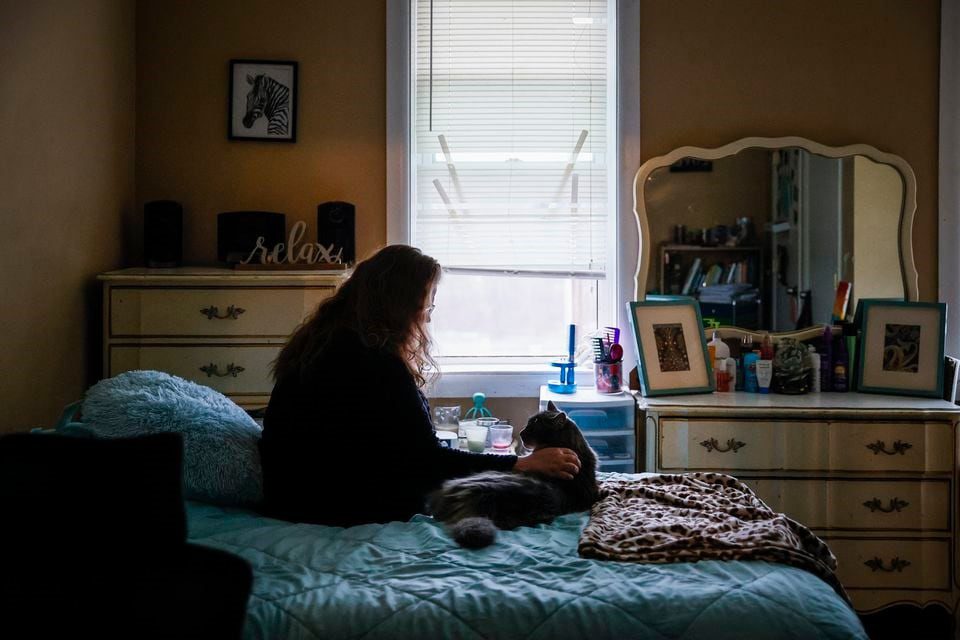

Holly White, 46, of Springfield first heard from DCF last September with a report that her 16-year-old daughter hadn’t attended school since April 2023. The teenager had not been going in person due to bullying that exacerbated her already severe anxiety, but the school had provided an online tutor, which allowed her to finish ninth grade. White had documents to prove her daughter had been receiving an education, but in October DCF still cited her for neglect. She feared the documents might not be enough.

“I was shutting down,” White remembered. “If I was able to fall asleep, I was having nightmares.”

White connected with Springfield’s family preservation program, and said having a parent advocate present during meetings with DCF workers was vital.

“I wanted to make sure all my i’s were dotted and all my t’s crossed,” White said. The parent advocate assigned to her case “was going to make sure everything turned out in the way it needed to be.”

White’s daughter said through her mother that DCF’s handling of her case made her feel ignored and unimportant.

Federal and state privacy laws prevent DCF from commenting on specific cases, a spokesperson said.

Family preservation programs walk a line between collaborating with DCF and challenging its actions. A DCF spokesperson said the programs can help “resolve stressors that can destabilize families and potentially lead to child abuse or neglect.”

In some cases, DCF refers families to the programs, and the lawyers who run them would like to build a better relationship with the agency.

“I certainly would like to see more come through DCF if they think their clients could benefit from our services,” said Maureen Lynch, an attorney with Northeast Legal Aid, which runs a family preservation program for Lawrence, Lowell, and Lynn.

Holly White participated in a diversion program that allowed her to access services and resources that resolved her case with DCF and helped her maintain custody of her child. ERIN CLARK/GLOBE STAFF

Child protection agencies wield enormous influence, including playing a pivotal role in determining whether a child should be separated from parents. Families involved in a DCF case typically don’t have a right to a court-appointed attorney until the agency takes steps to remove a child through a formal care and protection order, which may come months or years after a case is initiated.

“Child welfare, it is not an area of the law people traditionally think about due process,” said Emilie Cook, a lawyer with the Barton Child Law & Policy Center at Emory University School of Law, and one of the national leaders in the movement to reform child protection cases. “It comes from this paternalistic notion that we’re here to protect kids.”

The movement to put guardrails on child protection agencies’ expansive powers gained momentum as the COVID-19 pandemic and George Floyd protests brought national attention to issues of systemic racism and economic inequality, Cook said.

Living in foster care is associated with an increased risk of entering the criminal justice system and worse educational outcomes, state and national studies show.

“Even short removals into foster care create a trauma for children,” Blanchette said.

The law requires the agency to take immediate action, including potentially removing a child from home, if there is a reasonable belief that child is in danger, a DCF spokesperson said.

About 50 preventative legal aid programs exist nationally, Cook said, and are too new and too small to have robust data showing their effectiveness.

And their reach is minuscule for now. The Massachusetts programs have worked with just 110 families since 2021. By comparison, DCF opened 8,577 new cases in 2022, according to the agency’s annual report.

To maintain the existing programs, the organizations are looking for additional sources of funding. One possible partner, Elsen said, is the state’s public defender’s office, which is receiving $15 million in federal funds this year.

A spokesperson for the Committee for Public Counsel Services said the agency had not decided how that money will be used.

DCF closed White’s case in February with help from Blanchette and a parent advocate. It helped that White had documentation from her daughter’s psychiatrist that the teen should receive online learning. Now, Blanchette is working to overturn the negligence finding against White.

For White, the most frightening part was the feeling of being condemned for decisions she made to protect her daughter.

“I know the way it should be,” she said, “and I know we did everything to prove I’m not a bad parent.”