April 30, 2024

Bias of historic redlining in Springfield plain as day on map (Viewpoint)

BY MassLive

The Fair Housing Act became United States law in 1968 in order to end discrimination in the home rental and buying markets. Over the past 55 years, the act has fallen short of its purpose. From October 2021 to September 2022, the U.S Department of Housing and Urban Development received 11,741 complaints of discrimination across the country.

The Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination received 427 complaints about discrimination in state public and private housing markets from October 2022 to September 2023.

Not only is the act supposed to address discriminatory housing practices that have already happened, it also requires that HUD-funded organizations take “meaningful actions … [to] overcome patterns of segregation and foster inclusive communities.” This is what HUD and fair housing programs nationwide call Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing. In theory, the act’s enforcement measures and mandate to address systemic inequities should together end housing discrimination.

But this has not yet happened, including in Massachusetts.

The United States itself was built upon property theft. In 1823, the U.S. Supreme Court reasoned under the Doctrine of Discovery that white colonizers could own land and Indigenous people could only have occupancy rights to the same land. Ever since, the United States has excused its colonial actions and given itself continued permission to evict Indigenous people from their ancestral lands. Our country’s legal system relies on precedent – using past court opinions as guides for future decision-making. This means that modern understandings of property rights stem from these early cases. White supremacy is foundational to our nation’s property rights framework.

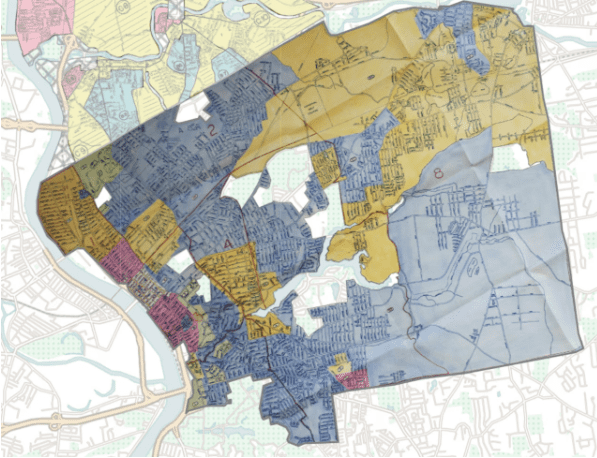

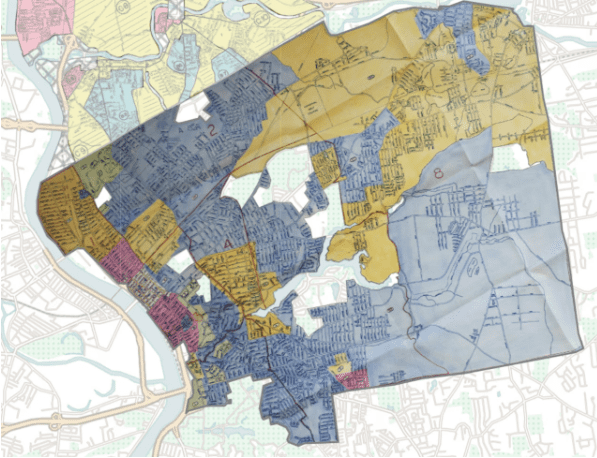

Springfield’s redline map is now available online through Mapping Inequality. This map, just like all other redline maps, shows us that systemic inequality is both an American legacy and an ongoing problem.

This map from the 1930s shows areas in red that were deemed unsuitable for investment.

When Springfield’s map was finalized in 1935, neighborhoods along the Connecticut River were considered “declining” (yellow) and “hazardous” (red). According to 2020 U.S. Census data, poverty rates in those neighborhoods range from 44.1% to 60.9%. Data also show that these same areas house the highest percentage of BIPOC individuals in the city.

As intended, redline maps told the federal government which neighborhoods were worthy of financial investment. They also directed which communities would struggle to economically recover during the Great Depression. Undoing centuries of systemic racism requires large-scale intentional action. At Community Legal Aid’s Fair Housing Project lawyers, testing coordinators and paralegals are affirmatively furthering fair housing through community education, testing, and legal advocacy.

The Fair Housing Project exists because people in Community Legal Aid’s central and western Massachusetts service areas need to know that they have a legal right to equal housing opportunity as well as access to free legal help in order to confidently assert those rights. Raising awareness of continued mistreatment can also incentivize people, communities, and decision-makers to demand change. The Fair Housing Project’s testing program is another affirmative tool meant to evaluate housing providers’ compliance with fair housing laws. Where there is evidence of discrimination, there are options for holding landlords accountable while advocating that their policy and practices align with anti-discrimination laws.

The Fair Housing Act’s promise to eliminate housing discrimination does not need to be empty. With collective effort, increased awareness, and creative problem-solving, we can work towards righting systemic injustice.

Nuri Sherif is the Fair Housing Testing Coordinator with Community Legal Aid in Worcester. The office handles cases in Central and Western Massachusetts.